Preceding the development of contemporary clogging in the second half of the twentieth century, there was an earlier tradition of step dancing in western North Carolina, and individual buckdancers and flatfoot dancers were once a common sight at community dances or wherever music was being played. These were not performances, but a form of social dance – a way to interact with other dancers and enjoy the music with one’s feet. While dancers shared certain characteristic movements, the footwork was not standardized, and this allowed for a wide variety of personal steps and styles. Some dancers were lively and percussive; others were subtle and smooth. These step dances have roots in earlier European, African, and Native American dance forms, and as a living tradition, they were not static. In the 1920s, many dancers adopted steps and movements from the Charleston, incorporating that dance into the tradition.

In 1992, I received a grant from the North Carolina Arts Council to document dancers in the western part of the state, who knew the older styles and had learned to dance before the standardization that came with the introduction of contemporary clogging. That fall and during the spring of 1993, I located, interviewed, and filmed more than forty dancers, ranging in age from fifty to eighty-five (the eldest was born in 1908). They included African American and Native American as well as European American dancers living in Buncombe, Burke, Clay, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Madison, Swain, Watauga, and Yancey Counties. The original videos have now been digitized, and with the support of sabbatical funding from Warren Wilson College, I have edited them into nineteen short films, featuring thirty-eight of the dancers. Here they are, arranged by county. Most are about five minutes in length; the longest two, involving multiple dancers, are just over seventeen minutes. (read more . . . )

Videos

Earl C. McElreath (1936–2016) lived in Leicester in Buncombe County, North Carolina. He grew up in a family of dancers, the most well known being Bill McElreath (1904–1974), who was a perennial favorite at Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville. Earl learned to dance by going to dances and watching the other dancers. He differentiates his freestyle “buckdancing,” which is based on a forward and back sliding motion, with his heels down, from the older style, in which dancers stayed up on the balls of their feet.

Music: Phil Jamison (banjo), Lawrence Dillingham (guitar), George Buckner (banjo)

Recorded: Candler, NC (June 12, 1993)

In 1993, I met a group of African American women at the Grove Street Senior Center in Asheville, North Carolina. These women, in their late 70s and early 80s, had grown up with jazz and swing music, and they had rejected the rural barn dances of their parents’ generation in favor of newer popular dances: the Charleston, the Two-Step, the Black Bottom, the Sand, the Hucklebuck, the Slow Drag, the Jitterbug, and the Electric Slide. Several of them speak of dancing to a “piccolo” (slang for jukebox).

Hattie Tribble (1913–2009) was born in Laurens, South Carolina, and she grew up in Greenville, where she learned to do the Charleston in school. After moving to Asheville, she continued to dance at house dances.

Ruth King (1911–2001) was likewise born in South Carolina, and she recalled going to dances at the Asheville Civic Center and at a local tobacco warehouse when she was young. She remembered dancing to Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Fats Domino, Cab Calloway, and many of the other bands that came through town. She incorporates some Charleston steps into her individual dancing as well as the Electric Slide. King also dances the Slow Drag with Hattie Tribble’s son, Harold Tribble (1933–1993). Having never received any formal dance lessons, she claims, “I was just born dancing.”

Juanita Jones (1914–2010) was born in Asheville, and like Ruth King, she referred to herself as a “born dancer.” In her youth, she attended house dances, where in addition to the Charleston, she danced the Jitterbug and the Black Bottom.

Lucille Smith (1915–2010) was born in nearby rural Rutherford County, North Carolina in 1915. She recalled barn dances taking place during her youth. Her parents, however, were religious and didn’t allow their children to dance. Consequently, Lucille would “slip” out of her parent’s house to go to house dances, where, dancing to a guitar, she learned the Charleston, the Black Bottom, the Sand, and the other popular dances of the day.

Clementine DeVigne (1914–2010) was born in Asheville, but moved to New York City, where she became a licensed nurse. She moved back to Asheville in the 1980s. DeVigne danced the Slow Drag and the Hucklebuck.

Viola Edgerton (1914–2000) was born in Rutherford County, North Carolina, but grew up in Asheville, where she learned the Charleston and the Two-Step.

Music: Robert Morgan

Recorded: Asheville, NC (May 25, 1993)

Robert “Buck” Buchanan (1927–1998) was born in Swain County, North Carolina, at Smokemont, a lumber town near Cherokee. When he was six or seven years old, this community was taken over for the creation of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park, and his family moved to the head of the Pigeon River in nearby Haywood County. Buchanan’s mother played the banjo, and both of his parents danced. House dances were common on Saturday nights, and he recalled dancing at age eight. By the time he was fifteen, he was performing in a dance group, the Foggy Mountain Cloggers, led by legendary dancer Sam Queen. Buchanan, who dances in tap shoes, refers to his style of dancing as “buckdancing.” He was filmed at his home in Burke County, where at the age of sixty-six, he was still active as a dancer – one with great stamina.

Music: Gary Johnson (banjo), Phil Jamison (guitar)

Recorded: Morganton, NC (April 25, 1993)

Benjamin Wayne Phillips (1915–2005), the proprietor of “The People’s Store,” an over-stocked antique store in Hayesville, North Carolina, grew up dancing in Clay County. As a youth, he attended box suppers, cakewalks, and house dances, where he danced old-time square dance figures. Phillips referred to his dancing as “buckdance” – “keeping time with the music,” “no two people do the same step.”

Music: Jim Ledford (fiddle), Phil Jamison (banjo)

Recorded: Hayesville, NC (April 26, 1993)

Robert Wesley “Chief” Howell (1912–2010) grew up on a farm at Jonathan Creek in Haywood County, North Carolina. He attended local house dances and barn dances as a child, and he acquired the name “Chief” during his first year of school, when he played an Indian chief in the school play. Howell learned how to dance from his uncle, Sam Queen, and by the time he was eighteen, he was performing at local dances with Queen’s Soco Gap Square Dancers. When this group was invited to perform for the King and Queen of England at the Roosevelt White House in 1939, however, he was not able to go due to his responsibilities on the farm. Howell subsequently coached a number of local dance teams, including the Dayco Cloggers (comprised of employees at Dayco rubber plant in Hazelwood) and a children’s group, known as the Maggie Valley Dancers. He later traveled and performed with a clogging team, the Carolina Cut-ups, and he frequently called public dances for tourists in nearby Maggie Valley. Here at the age of eighty, following a stroke, he is still eager to show off his “buck and wing” dancing at his home. As a part of this documentary video project, Howell was also filmed dancing and calling out square dance figures at a community center in Maggie Valley.

Music: Phil Jamison

Recorded: Waynesville, NC (May 24, 1993)

J. W. “Buck” Finney (1924–1996) grew up in Big Cove in Haywood County, North Carolina. His father was a logger, factory worker, and banjo player, and both of his parents were dancers. Finney recalled house dances as a child, and by the age of four or five, he had acquired name “Buck.” He later danced at the Canton Armory, where Sam Queen called out the dance figures from the floor. These included “Lady Round the Lady, Gent Don’t Go,” “Bird in the Cage,” “Georgia Rang-tang,” and “Open the Garden Gate.” Finney went on to perform with Queen’s Soco Gap Square Dancers, as well as other local dance teams, including the Haywood Mountaineers, the Southern Appalachian Cloggers, and the Rough Creek Cloggers. In 1966, he performed, along with Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith, in the Tex Ritter film, The Girl from Tobacco Row, and his dancing can also be seen in Full of Life A-Dancin,’ a 1978 documentary film about the Southern Appalachian Cloggers. Finney referred to his dancing as “flatfooting,” though he also performs a high-stepping signature step of his own creation that he calls “The Chicken.”

Music: Phil Jamison

Recorded: Hazelwood, NC (May 24, 1993)

Haywood County, North Carolina has long been known for its dancing. This was the home of Sam Queen’s Soco Gap Square Dancers, who were invited, in 1939, to perform for the king and queen of England at the Roosevelt White House. In 1993, former members of Queen’s dance team, including Richard Queen (Sam Queen’s son), John Reeves and Robert Howell (Sam Queen’s nephews), and Catherine McCrary, joined with other Haywood County dancers at a community center in Maggie Valley to demonstrate their steps and styles for the camera. By this time, steps from the Charleston (1920s) and clogging (1950s) had been incorporated into the local tradition alongside the older style of buckdancing. Each dancer performs solo, and then of the eight dancers form a set to demonstrate a few of the mountain square dance figures, called by Robert “Chief” Howell.

John Reeves (1918-1995) of Lake Junaluska recalled going to his first square dance at age fourteen. He learned to dance from his uncle Sam Queen, and before long he was performing with Queen’s Soco Gap Square Dancers. Reeves referred to his style of dancing, in which he stays up on his toes, as the “Buck and Wing,” and he had names for many of his steps: “The Walk,” “The Running Walk,” “The Broken Wing,” “Wring the Chicken’s Neck,” “Dust the Pigeon Toe,” “The Shuffle,” “The Double Shuffle,” and “The Backstep.” Reeve’s dancing can also be seen in Mike Seeger’s 1987 documentary film, Talking Feet, online at: http://www.folkstreams.net/film,121

Catherine McCrary (1923-2006), Maggie Valley

Troy D. Cutshaw (1916-2000), Waynesville

Pearl Owen (1920-2004), Waynesville

Dallas Mathis (1917-2003), Maggie Valley

Alaska Pressley (b. 1923), Maggie Valley

J. Claude Caldwell (b. 1931)

Hattie Caldwell Davis (b. 1927), Maggie Valley

Gene Ferguson (b. 1935), Waynesville

Marlene Blalock (b. 1935), Maggie Valley

Richard Queen (1918–2004), Maggie Valley

Lois Pryor Queen (1922-2008), Maggie Valley

Robert “Chief” Howell (1912-2010), Maggie Valley. Howell was also filmed dancing at his home at Jonathon Creek.

Music: Liz Shaw (fiddle), Lynn Shaw (fiddle and guitar), Trevor Stuart (fiddle and guitar), Travis Stuart (banjo and bass)

Recorded: Maggie Valley, NC (May 7, 1993)

Berta Frady (1908–1995) of Henderson County, North Carolina started dancing at family corn shuckings when she was ten years old. She later danced with the Limestone Dance Team with whom she competed at Asheville’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. She recalls, in her youth, dancing the Charleston, the Two-Step and the Turkey Trot as well as square dance figures. Here, at age eighty-five, she also demonstrates patting (aka Hambone) as a way to keep time with the music. Frady was filmed at the home of dancer James Kesterson.

Music: Phil Jamison

Recorded: Hendersonville, NC (April 2, 1993)

Ruth Mosteller (1932-2019) grew up dancing in the house that was built by her grandfather in the 1880s in the Barker’s Creek community of Jackson County, North Carolina. She comes from a long line of dancers that includes her mother, Lottie Jones, several uncles, grandparents, and great grandparents. Her father, Ben Jones, played the fiddle, banjo, and guitar. At age ten, Ruth performed on stage in a dance contest at the annual Farmers Federation picnic in nearby Sylva, and at age sixteen, she moved to Raleigh to attend business school. There, after being shown a few tap dance steps, and inspired by Gene Kelly’s performance in the 1955 film, It's Always Fair Weather, she learned to tap dance in roller skates. In 1970, she returned to her family home in western North Carolina and married master fiddler Gar Mosteller. Ruth is a creative dancer, whose unique style of freestyle clogging is a combination of buckdancing, the Charleston (which she learned as a child), tap dancing, and steps of her own invention. One of her dance creations, the “Truckin’-Chicken-Mashed Potato,” is a combination of the “Mashed Potato,” which she learned from an African American woman in Raleigh, and two other dances.

Music: Gar Mosteller (fiddle), Phil Jamison (banjo, guitar)

Recorded: Whittier, NC (February 20, 1993)

Betty Garland (b. 1933) of Jackson County, North Carolina, is a self-taught dancer, who learned at home, dancing to records and a battery-powered radio. When she was growing up, her family would invite the neighbors over for house dances, and her mother would make chicken and dumplings. Betty wears tap on her shoes in order to hear her steps more clearly, and she refers to her dancing as “freestyle clogging” – “I don’t know what I do . . . I just do my thing.” On summer nights throughout the 1990s, Betty and her cousin, Ruth Mosteller, could often be found on the open-air dance platforms in nearby Cherokee, where they participated in clogging, couple dances, square dances, and broom dances.

Music: Gar Mosteller (fiddle), Phil Jamison (guitar)

Recorded: Sylva, NC (April 23, 1993)

Mary Jane Queen (1914–2007) grew up in a musical family in the Caney Fork community of Jackson County, North Carolina. Her father, Jim Prince, from whom Mary Jane learned the banjo, played the fiddle and banjo, and her mother, Clearsy Anne Nicholson, was a singer and dancer. Mary Jane referred to her own dancing as “buckdancing,” but she also danced Charleston steps that she learned in the late 1920s. Known for her ballad singing, Queen received the North Carolina Heritage Award in 1993, and subsequently, she served as the model for Viney Butler, a singer of old mountain ballads in the 2000 film Songcatcher. In 2007, shortly after her death, she was honored with the National Heritage Award. See: http://www.blueridgeheritage.com/traditional-artist-directory/mary-jane-queen

Music: Delbert Queen (fiddle), Phil Jamison (banjo)

Recorded: Cullowhee, NC (June 20, 1993)

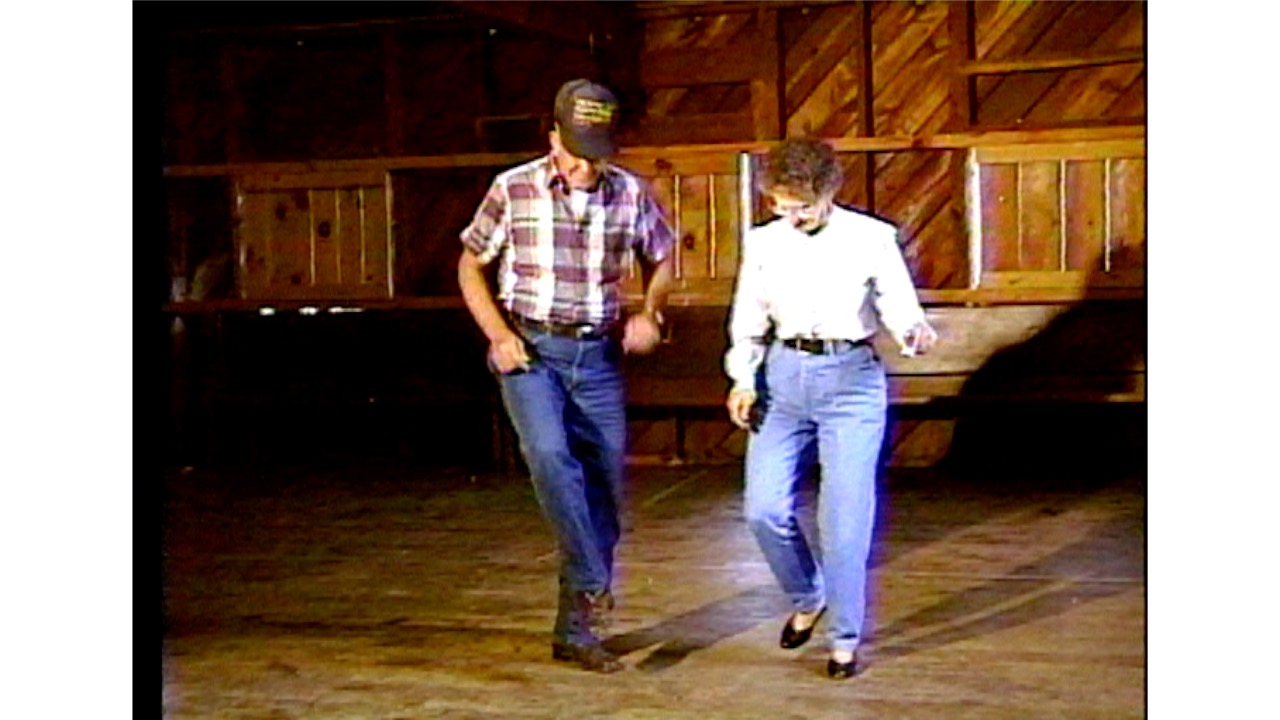

L. C. King was born in 1943 in Madison County, North Carolina. He learned to dance from his father, and he describes his smooth, rhythmic dance style as “old-time flatfoot dancing” and “a little bit of tap.” L. C. was working in a furniture store in Candler at the time of this project, so that is where he and another dancer, Earl McElreath, were filmed.

Music: Phil Jamison (banjo), Lawrence Dillingham (guitar), George Buckner (banjo)

Recorded: Candler, NC (June 12, 1993)

Emma Lou Wambles (1933–2010) of Madison County, North Carolina taught herself to dance at home, listening to the “Saturday Night Roundup,” a weekly radio show that was broadcast from Asheville on WWNC. When she was growing up, community dances following workings (log rollings, barn raisings, corn shuckings, etc.) were a thing of the past, and public dances, which had become rough, were to be avoided.

Music: John Herrmann (fiddle), Jerry Adams (banjo), Hilary Dirlam (guitar)

Recorded: Marshall, NC (April 22, 1993)

Francis Pauline Ray Zimmerman (1919–2011) grew up in a musical family in Madison County, North Carolina. Her brothers Byard Ray and Otis Ray played fiddle and guitar, and her mother, Rila Wallin, was a dancer. As a young girl, Pauline attended house dances as well as street dances in Hot Springs and Marshall. Zimmerman was a self-taught dancer, who referred to her dancing as “the jubilant spirit within me,” “my own style of dancing.” Her dance steps are a mix of buckdance and clogging, along with some Charleston steps. She first learned Charleston steps from a cousin who had visited relatives in South Carolina in the late 1920s, but she also saw it being done in movies. She also performs a step, known locally as the “Shelton Laurel Backstep,” that was supposedly named by loggers who danced on tree stumps.

Music: John Herrmann (fiddle), Jerry Adams (banjo), Hilary Dirlam (guitar)

Recorded: Marshall, NC (April 22, 1993)

The Cooper brothers, Jim (1929–2016), Candler (b. 1931), and Robert (b. 1939), grew up on the Cherokee Indian Reservation in Cherokee, North Carolina. Their father, Arnold Cooper, was the leader of the Smoky Mountain Dance Team, and as children, they performed on exhibition square dance teams. Jim and Chandler both also performed with Sam Queen’s Soco Gap Dance Team. Jim Cooper attended Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah (1952–56), and in 1956, he introduced North Carolina square dancing and clogging to what later became the university’s folk dance ensemble. Jim and Chandler differentiate between their buckdancing, which is done on the balls of the feet, and the later clogging of the 1950s, when local dancers adopted a heavier style and it became common to wear taps on the shoes. The Coopers were filmed one Saturday night at the Smoky Mountain Jamboree, a music venue catering to tourists in Cherokee that featured a band led by their nephew, Rick Morris.

Music: Rick Morris Band

Recorded: Cherokee, NC (June 18, 1993)

Robert Patrick (Pat) Maney (1925–2006) of Swain County, North Carolina, grew up in a family of Scots-Irish ancestry. His mother was religious and opposed to dancing, but his father was a musician and buckdancer. Maney described his dancing as a mixture of clogging and flatfooting, though he points out that it used to be called “buckdancing.” In the 1940s, he danced on the Smoky Mountain Square Dance Team with Cherokee-Scots-Irish dancer Jim Cooper.

Music: Gar Mosteller (fiddle), Phil Jamison (guitar)

Recorded: Sylva, NC (April 23, 1993)

Robert Lee Dotson (1923–2015) and Myrtle Cook Dotson (1921–2008) both grew up in the community of Sugar Grove in Watauga County, North Carolina. When they were young, dancing was common at house dances and box suppers. Robert's grandfather, Ab Dotson, as well as both of his parents, Don Dotson and Bina Jane Hicks Dotson, played old-time banjo and were dancers. Robert characterized his dancing as “flatfooting,” and Myrtle referred to hers as the Charleston, a dance that was popular with women of her generation. In the late 1970s, Robert became a mentor to the Green Grass Cloggers. This young dance group from North Carolina, popularized a step, called the “Walking Step,” that was inspired by Robert’s dancing and now known by dancers across the country. In 1994, Robert Dotson received the North Carolina Heritage Award.

Music: Cecil Gurganus (fiddle), Mary Greene (guitar), Phil Jamison (banjo)

Recorded: Valle Crucis, NC (May 10, 1993)

Ora Watson (1911–2008) grew up in the Sugar Grove community of Watauga County, North Carolina. Her father, Arthur Isaacs, played old-time fiddle and banjo, and he was also a singer and dancer. Her mother, Mary Fletcher Isaacs, was a gospel singer in the church. By age eleven, Ora was adept on fiddle, and she and her sister and a cousin formed a band. Calling themselves the Isaacs Sisters, they played for parties, house dances, church socials, cakewalks, and fiddlers' conventions. Watson referred to her dancing as “buckdance” or “flatfooting,” but she also included Charleston steps that she learned in her youth. Active as a dancer and a musician throughout her long life, she could still fiddle and dance at the same time, even at the age of eighty-two. Watson received the North Carolina Heritage Award in 1995.

Music: Cecil Gurganus (fiddle), Mary Greene (guitar), Phil Jamison (banjo)

Recorded: Valle Crucis, NC (May 10, 1993)

Biss Honeycutt (1909–2000) of Yancey County, North Carolina told me that he was born near Burnsville in a mountain cabin that spanned the Tennessee state line. His father, Tom Honeycutt, was a horse trader and a fiddler, and his mother was a dancer, who could dance the “double shuffle.” Honeycutt grew up with house dances and learned to dance as a child. In 1921, the family moved to Rutherford County, where his mother worked in a cotton mill. He later lived in Marion, North Carolina (for six years before 1941) and in Detroit (from 1943 until 1956) before he moving back to Yancey County. Every time I visited Honeycutt at his home, he was dressed in a white suit, white shoes, and a white hat. At age eighty-four, and with only one lung, he was clearly past his prime as a dancer, but he was still willing to demonstrate his old-time buckdancing: the “backstep,” “heel-and-toe,” “shoe shine,” “walkin’ the log,” and other steps.

Music: Honeycutt Brothers

Recorded: Burnsville, NC (April 3, 1993)

(project narrative continued)

When I undertook this documentary project, I was a stay-at-home dad, and this was something that I could do accompanied by my eighteen-month-old daughter, Sarah. That fall and spring, the two of us logged many miles throughout western North Carolina in search of dancers. Musicians and dancers, whom I already knew, provided many names, and one dancer led us to another. I also visited regional music venues and asked about dancers at senior centers. There were, of course, many dead ends along the way. More than once, I was informed that the “greatest dancer that ever lived” had recently passed away. One of the more memorable dead ends was Ella Sequoyah, an elderly buckdancer who lived in the Big Cove community on the Cherokee Indian Reservation in Swain County. She didn’t have a phone, but I was able to call a neighbor, who would deliver messages, and we eventually arranged for a time to visit. I looked forward to meeting her. When I arrived at her home, however, I was disappointed to find out that she had recently broken her ankle and could no longer dance. She and her granddaughter were sitting there watching “Wayne’s World” (her favorite movie), and I recall seeing numerous buckdancing trophies, which she had won over the years, up on a shelf. Sadly, I was not able to see her dance or film her.

Whenever possible, I visited dancers at their homes prior to filming, and it turned out having a baby along with me, rather than being a hindrance, was an unintended advantage that opened many doors. More than once Sarah and I ventured along a back county road up some holler to get to a dancer’s home, and I would knock on the door with my banjo in one hand and a baby in my other arm. The door would fly open, and we would immediately be invited inside with the words, “Oh, let me see that baby!” After visiting for a few minutes, I would take out my banjo and begin to play, and Sarah (the baby) would start to shuffle her feet. Invariably, the dancer we were visiting would get up and dance with her, and I, an unknown male and a complete stranger, could assess in a very short time after arriving whether or not this dancer was worth filming. It worked like a charm, time after time! I would then conduct a preliminary audio interview to obtain background information, personal stories, perspectives, and biographical information. (Excerpts from many of these interviews appear in my book, Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics.) Following this, if the dancer was willing and able, we would agree on a time and place for filming. Some of the dancers had specific musicians or recorded music they wanted to dance to; for others, I played the banjo. The filming, which was done by Howard Hill and David Brewin, of the Mountain Heritage Center at Western Carolina University, resulted in approximately thirteen hours of unedited video. This footage includes dancing as well as interviews and some shots of the musicians and the dancers’ homes. At most locations two cameras were used: one showing a full body view from the front and the other, from the side, focused at just the feet. These videotapes (in the High-8 and S-VHS formats) as well as audiocassettes of the dancers’ interviews are now part of the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill (Collection Number: 20389), and while they have been available to researchers, until now, they have not been readily accessible to dancers, or others, who may wish to study or learn from them. In addition to this website, I have posted these dance videos on a YouTube channel: Western North Carolina Buckdancers, Flatfooters, and Charleston Dancers (1993). My intention is that they will serve as a complement to Mike Seeger’s 1987 film Talking Feet (Smithsonian Folkways DVD SFW48006), which was the original model and inspiration for this project. (Talking Feet is now also available online at Folkstreams.net.)

Although I was able to locate and document over forty dancers, I was aware of many others (now deceased), whom I did not have the time or resources to film. There are also a number of counties that I never made it to. The dancers we were able to film, however, demonstrate the diversity of steps and personal styles that existed prior to the advent of contemporary clogging, when dancing was still common in local communities throughout western North Carolina. These dancers were my informants. They became my friends and my mentors, and sadly most all of them are now deceased. I am pleased, however, to finally be able to share their dancing, their wisdom, and their stories of earlier times in the southern mountains. To these dancers, I dedicate this project.